Introduction

Women’s involvement in the labor market has changed in several notable ways over the past several decades. All over the world, discriminatory laws continue to threaten women’s economic security, career growth, and work–life balance. Such barriers to employment and entrepreneurship at every stage of life limit equality of opportunity, creating a business environment that does not adequately support working women.

Today, women have just three-quarters of the legal rights of men; in 1970, it was less than half. Over 2 billion women don’t have the same employment options as men. At the current rate, it will take about a century to close the global pay gap. The Women, Business and the Law 2020 report presented results on how laws have changed since 1970. This project explores global gender wage disparity holistically, understands the economic indicators such as gender equality index, GDP, inheritance rights, financial independence and gauges if there exists a relationship between them and wage inequality. An analysis on the aid set aside for bridging this gap is also explored. We aim to provide a detailed overview of how the employment numbers have changed over the last 72 years and the laws/reforms that have aided their improvements over the years.

Why is this important?

Women’s impact doesn’t stop with individual companies and organizations.

Studies show that increasing women’s participation in the economy is good for the economy.

In OECD countries, if the female employment rates were raised to match Sweden, it would lead to a GDP

increase equivalent to $6 trillion. Gender pay gaps end up costing the economy. A range of public policies and

societal, educational, and labour market transformations over generations

have done little to close the gender wage gap around the world. Today, the wage gap between the median

earnings of full-time working women and men stands at 13%, on average, across OECD countries.

Results

Gender Wage Disparity in Numbers

The gender pay gap (or the gender wage gap) is a metric that tells us the difference in pay (or wages, or income) between women and men. It’s a measure of inequality and captures a concept that is broader than the concept of equal pay for equal work.

According to pew research1, much of this gap has been explained by measurable factors such as educational attainment, occupational segregation and work experience. The narrowing of the gap is attributable in large part to gains women have made in each of these dimensions. Even though women have increased their presence in higher-paying jobs traditionally dominated by men, such as professional and managerial positions, women as a whole continue to be overrepresented in lower-paying occupations relative to their share of the workforce.

Controlled Wages and Uncontrolled Wages

The controlled gender pay gap is $0.99 for every $1 men make, which is one cent closer to equal but still not equal. The controlled gender pay gap tells us what women earn compared to men when all compensable factors are accounted for such as job title, education, experience, industry, job level, and hours worked. In other words, women who are doing the same job as a man, with the exact same qualifications as a man, are still paid one percent less than men at the median. The closing of the controlled gender pay gap has been extremely slow, shrinking by only a fraction of one percent year over year. It has shrunk a total of $0.02 since 20152

Findings

In 2022, the uncontrolled gender pay gap is $0.82 for every $1 that men make, which is the same as last year. The uncontrolled gender pay gap as the name suggests do not take into account measureable factors such as job title, education, experience, industry, job level, and hours worked.

Gender Inequality Index

The Human Development Report produced by the UN includes a composite index that captures gender inequalities across several dimensions, including economic status. This index, called the Gender Inequality Index, measures inequalities in three dimensions: reproductive health (based on maternal mortality ratio and adolescent birth rates); empowerment (based on proportion of parliamentary seats occupied by females and proportion of adult females aged 25 years and older with at least some secondary education); and economic status (based on labour market participation rates of female and male populations aged 15 years and older). The map shows scores, country by country.

Findings

According to the Gender Inequality Index (GII), Switzerland was the most gender equal country in the world. Numbers on how long it will take to close gender gaps highly differ between regions. In Western Europe it is estimated that it will take around 52 years to achieve equality between the genders. In South Asia, on the other hand, it is supposed to take 195 years. New data shows that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased female poverty worldwide and widened the gender poverty gap even further. Heightened female poverty will also negatively impact the Gender Inequality Index (GII)3

Change in Gender Wage Disparity from 1980 - 2010

Here we further detail on the contribution of particular labor-market characteristics to the gender wage gap. Specifically, it shows the fraction of the total gender wage gap in 1980 and 2010 accounted for by gender differences in each group of variables for both the human capital and full specifications

Gender disparity has been increasing with respect to certain factors such as race, Occupation but has reduced in parts thanks to Education. As we can see there are unexplained reason why it still persists, pointing to the lack of data in this area.

Findings

Chart exemplifies following4 :-

- By 2010, due to the education reversal, women’s higher level of education slightly raised their relative wage.

- Gender differences in occupation accounted for a larger pay gap in 2010 than in 1980. However, while women upgraded their occupations during this period, the wage consequences of gender differences in occupations became larger as well

- The continued importance of occupation and industry in accounting for the gender gap, and the rise in the relative importance of these factors, suggests that future research on explanations might fruitfully focus on gender differences in employment distributions and their causes

- The "unexplained" percentage refers to the residual that remains after all other factors are accounted for – it is often seen as discrimination.

Gender Wage Disparity across Age

The United States Census Bureau defines the pay gap as the ratio between median wages – that is, they measure the gap by calculating the wages of men and women at the middle of the earnings distribution, and dividing them.

Findings

Gender wage becomes more pronounced after 44 for uncontrolled wage gap. The controlled wage gap is the same after 29 years and above.

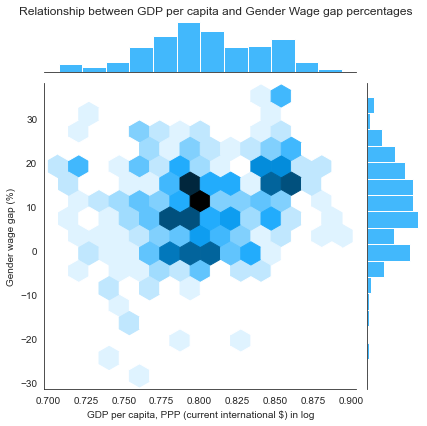

Analysis of Relationship between GDP and Gender Wage Gap

Here, we are trying to analyze the relationship between GDP per capita and Gender Wage Gap. As we can see there is a weak positive correlation between GDP per capita and the gender pay gap. However, the chart shows that the relationship is not really linear. Actually, middle-income countries tend to have the smallest pay gap. The fact that middle-income countries have low gender wage gaps is, to a large extent, the result of selection of women into employment.

Findings

Rather than reflect greater equality, the lower wage gaps observed in some countries could indicate that only women with certain characteristics – for instance, with no husband or children – are entering the workforce.

Change in Representation of Women in Top 10% Income Group

Despite having fallen in recent decades, there remains a substantial pay gap between the average wages of men and women. But what does gender inequality look like if we focus on the very top of the income distribution and is there any evidence of so-called glass ceiling?

Findings

While investment income tends to make up a larger share of the total income of rich individuals in general, the authors found this to be particularly marked in the case of women in top income groups. We can find that for the top 10% income group the change is very slow even in the high income countries.

Regional Averages of Composite Gender Equality Index

The gender equality index is based on gender ratios across four dimensions:

- Health

- Socio-economic resources

- Gender disparities in the household

- Gender disparities in politics

Findings

From the chart below, the trend is in the right direction except for Easter Europe during 1980's which can be attributed to the aftermath of the Fall of Berlin wall and the civil discord that arose as a result of it.

Change in Women's Participation in the Workforce

As time progressed, attitudes about women working and their employment prospects changed. Between the 1930s and mid-1970s, women’s participation in the economy continued to rise, with the gains primarily owing to an increase in work among married women. By 1970, 50 percent of single women and 40 percent of married women were participating in the labor force. Several factors contributed to this rise. The datasets are analyzed to understand how gender dynamics has changed in the labor force and potential reasons for the change.

Has Female Participation in Labor Force Grew Remarkably in the 20th Century?

The line plot depicts the changes in the female

labor force participation rates from 1960 to 2020.

The female labor force participation rate corresponds to the proportion of the female population aged 15 and older

that

are economically active. The trend line for United States is highlighted in blue color and the dropdown on the top

right corner gives user the ability to select different

countries and analyze the trends.

Findings

The visualization shows that there are positive trends across all the major countries. Looking at the plot, it is evident from that the 20th century saw a radical increase in the number of women participating in labor force across all the major countries although the growth in participation began at different points in time, and proceeded at different rates for different countries.Moreover, the plot helps in better understanding of where United States stands when compared to some of the other countries with the better Female Labor force participation rates in the world. From the chart, we can understand that a few countries have been consistent in ratio improvement when compared to US. Another interesting aspect is how the ratio in the United States remained constant after 2000.

Analyzing Female Participation in Labor Force in the USA, by Marital Status

The plot illustrates the changes in the

female labor force participation rates in United states by different Marital States from 1975-2020.

Findings

From the chart, we can clearly see that the increase in the labor force participation rate may be attributed to an increase in participation among married women. Married women drove the increase in female labor force participation in the United States. Better work policies for women and favorable maternity policies have helped increase participation among married women.Has Female Employment Grown Together with Rising Female Participation?

As the Labor force participation comprises both employed and unemployed people searching for work, this plot illustrates the female employment-to-population ratios across the world. The bar plot shows how the female employment to population ratio changed for the top 10 countries by Gender equality.

Findings

A couple of interesting observations are :a. In general, the average ratio for the top 10 countries has improved over the past 25 years showing how global policies could have helped improve the ratios.

b. The Female employment to population ratio has remained almost constant over the past 25 years for Iceland while other countries have improved their ratios to match Iceland.

c. The US was #2 in terms of ranking in 1996 but has gradually slipped to #8 by 2022.

Does Women participation in Labor force tend to be lower than that of Men?

This world map shows the ratio between female and male labor participation rates over the years. A ratio of 100% indicates that female and male labor participation rate is the same and a higher ratio means a better female labor participation rate. The slider to the bottom of the chart allow users to see how data changes over time on the world map.

Findings

When we move from 1990 to 2022, we can see how the world is gradually moving from Blue (indicating a ratio below 50%) to red (indicating a ratio above 50%). However, in some countries such as Syria or Algeria, the relationship is below 25%. The most significant improvement is in South America where there has been a marked change which reflects how Globalization has opened these markets and has helped drive better work conditions for women in these countries.Measuring Laws and Regulations

The pursuit of gender equality is an uphill battle. The recent OECD assessment of how well countries are doing in implementing policy measures aimed at reaching gender equality goals is crystal clear: they need to do more. In particular, despite major improvements in the education of young girls, the rising labour force participation of women and widespread laws against gender discrimination, women’s position in the labour market severely lags behind that of men, and the gender gap in labour income remains a global phenomenon.

To demonstrate where laws facilitate or hinder women’s economic participation, Women, Business and the Law 2020 presented an index covering 190 economies and structured around the life cycle of a working woman. To ensure comparability, the woman in question is assumed to reside in the main business city of her economy and to be employed in the formal sector. Below are the 8 indicators:

Women, Business and the Law (WBL) measures legal differences between men's and women's access to economic opportunities in 190 economies. Thirty-five aspects of the law are scored across eight indicators of four or five binary questions. Each indicator represents a different phase of a woman's career.

Regulations by Country (1970-2022)

The chart on the left shows the total laws passed with respect to gender equality and the WBL index score. A higher WBL index score indicates higher gender equality in the country. The chart on the left shows a timeline of the reforms passed in each country and when the mouse is hovered over any point the details of the reform including it's description, the year it was made and whether it was in a positive or negative direction can be seen. This chart can be used to compare laws among countries with higher scores v/s those with lower scores. It can help the viewer take inspiration as to what laws are made in countries with higher equality as well as laws made in neighboring countries with similar cultural backgrounds that can be applied successfully in a given country.

Findings

Legal changes enacted in the Middle East and North Africa resulted in 10 positive data changes, more than any other region. Despite its low scores, the region advanced the most because of its reform efforts, with 25 percent of economies implementing at least one reform. Economies in Europe and Central Asia also implemented reforms, despite having scores above the global average, with 17 percent changing at least one law to improve legal equality for women. Progress in the rest of the world was slower.

12 economies—Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Latvia, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden—score 100, meaning that women are on an equal legal standing with men across all of the areas measured.

Analysis of Progression in Index Scores by Country from 1970-2021

The Women, Business and the Law index measures explicit discrimination in the law,

legal rights, and the provision of certain benefits, areas in which reforms can bolster

women’s labor force participation. Governments can use this framework to identify

barriers to women’s success, remove them, and boost economic inclusion. The eight Women, Business and the Law indicators coincide with the milestones that many women experience throughout

their adult lives. Questions included in the indicators were chosen based on evidence from the economic literature as well as

statistically significant associations with outcomes related to women’s economic empowerment, such as employment and

business ownership.

The graph below visualizes the progressions of index scores for each of the above indicators by country.

Findings

The Mobility, Workplace, Marriage, Entrepreneurship, and Assets indicators have an average global score above 80, meaning that most economies have removed restrictions or introduced the relevant legal rights and protections measured by these indicators. Average scores are lower for the Pay, Parenthood, and Pension indicators. Parenthood, with an average score of 55.6, has the most room to improve, followed by the Pay indicator.

Parenthood

Childbirth and early career events play a crucial role in the widening of gender disparities over the life course. Not only do women experience slightly fewer job changes than men on average, but the nature of their labour market mobility also differs from that of men. Women do experience in-work transitions – change of employer, job or contract type – but less often than men, and they tend to have fewer in-work transitions that occur at the beginning of men’s careers. By contrast, in almost all countries, women move part-time and enter inactivity more often than men, although they also exit inactivity more often too. Fewer in-work transitions for women than men during the early years of their careers, particularly around the time of childbirth, translate into lower earnings growth.

On average, the gender gap in the career length of parents is more than twice as large as that of childless workers. Recent research supports this point, indicating that paternity leave is associated with greater relationship stability. That may be because when fathers take leave, it signals a greater investment in family life—reducing the burden on the mother and strengthening parental relationships.

by Country

The above two charts represents the number of paid paternity and maternity leaves granted by federal governments across different countries through each of the five continents. Until a few years, paternal leaves were not provided by any country and only recently, federal governments have begun to recognize Paternal leaves as an important policy.

Findings

- Africa: African countries have accounted well for women's rights in terms of providing paid maternity leaves to mothers. But have not given the same or even remotely proportional rights to men, with only South Africa and Kenya providing a paternity leave of 14 days to fathers.

- Oceania: The only country in the Oceania region to provide paid maternity leave is Fiji and paid paternity leave is Australia.

- United States: Being one of the most developed countries in the world, United States does not offer federal paid maternal or paternal leaves. Both parents work full-time in almost half all two-parent families. In April 2021, US President Joe Biden proposed a $225bn (£163bn) package of paid family and medical leave benefits that would allow workers to take up to 12 weeks paid leave to care for a new-born or family member.

- Europe: All of the major countries in Europe have substantial amount of paid maternity and paid paternity leaves with Ireland having the highest number of paid maternity leaves and Spain with highest number of paid paternity leaves.

Summary of Media Coverage

It is important to summarize what is currently being said about the wage gap to be updated on the topics and people being spoken about as well as the demands of people. News articles tend to have more of a report of the current status whereas 'tweets' have tend to be the opinion of the general public on the matter. Speeches given by political leaders show their standing on the matter. If we can find out what peoples concerns are, what the need and leaders that can help efforts can be focused in that direction. The summary chart here is made using news articles and 'tweets' written from January 2022 to April 2022 and the political speeches are from US politicians since the year 2000 upto now. Ideally it would be benficial to regularly update these charts to be current so viewers can have their own insights and conclusions.Twitter, News & Policial Speeches

Findings

Few words remain common in all three groups for e.g.: 'women', 'gender', 'equal'. Some words are interesting unique to each group these are discussed below:-

News:

- Pandemic and Covid: A few articles and analysis suggest that women were affected more during the pandemic than men. The participation of women in the work force decreased during the pandemic. Link to Article

-

Twitter:

- Soccer: Gender wage gap in sports is one of the highest. Recently the salary offered to women soccer players has been widely discussed on Twitter.

- Transparency: Tweets are talking about a need of transparency with respect to the salaries given to women and men.

- UK and EU: EU recently passed a law that companies with more than 50 employees are obliged to be obliged to report on gender pay gap. Gender action plan to be developed when pay gap is higher than 2.5%. Link to Article

- Salesforce: The company has gone on record to talk about the gender wage disparity within the company and has spoken about the steps it has taken to erase the pay gap.

-

Political Speeches:

- Obama, Biden, Harris: Both Presidents Obama and Biden as well as Vice President Harris have given speeches on gender wage disparity and equal pay. The Paycheck Fairness Act introduced by democrats was blocked in June 2021 Link to Article

Discussion

Awareness of gender issues has primarily been brought about as a result of the work of the women’s movement and of feminist politics, which includes work on gender equality, challenging the status and roles of women and men in society, and addressing the creation of gendered stereotypes. For this reason, there is a tendency to associate gender with women and women’s issues alone. Without bias and one-sided opinions, this project addresses the gender disparity issues with both men and women.

People may be highly attuned to signs of gender in the environment, while not necessarily being able to reflect on how these signs have become gendered. By means of this project, the important issues across all areas of gender bias have been raised and given substantial data driven evidence for.

Why should we care about gender equality?

Advancing gender equality is critical to all areas of a healthy society, from reducing poverty to promoting the health, education, protection and the well-being of girls and boys. Investing in education programmes for girls and increasing the age at which they marry can return $5 for every dollar spent. Investing in programs improving income-generating activities for women can return $7 dollars for every dollar spent.

Why is it important to take gender concerns into account in programme design and implementation?

There are two very important reasons. First, there are differences between the roles of men and women, differences that demand different approaches. Second, there is systemic inequality between men and women. This pattern of inequality is a constraint to the progress of any society because it limits the opportunities of one-half of its population.Understanding and addressing this inherit inequality will lead towards better policy making, a more fairer justice and judicial systems and a better work life balance for both men and women.

What can we do to fix these issues?

If you are a girl, you can stay in school, help empower your female classmates to do the same and fight for your right to access sexual and reproductive health services. If you are a woman, you can address unconscious biases and implicit associations that form an unintended and often an invisible barrier to equal opportunity. If you are a man or a boy, you can work alongside women and girls to achieve gender equality and embrace healthy, respectful relationships.

The gender pay gap measures inequality but not necessarily discrimination.

Through the visualizations and analysis in this project, we hope the readers develop an unbiased opinion towards gender equality, understand both sides of the coin and reflect on what has been done in the past and what can be improved for the next generations.

Conclusion

Wage disparity based on race, age and gender is an prevalent issue that is being addressed albeit at a glacial pace. It is imperative that we understand that issue exists so that we can work towards eliminating it. Countries with higher GDP also has gender wage disparity but the fact that we have data and studies are being made on it is a step in the right direction.

The increase in women's participation in the workforce was arguably the most significant change in the economy in the past century. Women's increased labor force participation represents a significant change in the U.S. economy since 1960. It can be said that most of the long-run increase in the participation of women in the labor force in the United States is attributed specifically due to an increase in the participation of married women. However, the analysis also shows that the growth in the United States as well as some other rich countries has slowed down considerably or even stopped at the turn of the 21st century. Also, despite recent growth in female participation rates, men still tend to participate in labor markets more frequently than women in most of the countries.

Nineteen economies score 0 on Parenthood, meaning that they do not have any of the good practices measured by this indicator (leave for mothers of at least 14 weeks, which is fully administered by the government, leave for fathers, parental leave, and prohibition of dismissal of pregnant women). Only 31 out of 190 economies score 100.

Six out of the seven regions improved their scores and reduced the gaps in legal rights and opportunities for women, at least on the books. The Middle East and North Africa had the largest improvement, followed by SubSaharan Africa, Europe and Central Asia, and East Asia and the Pacific. South Asia’s average score remains unchanged from the previous years.

We hope that the readers can utilize the information presented here in making informed decisions on disparity that does not have merit and collectively do our part.